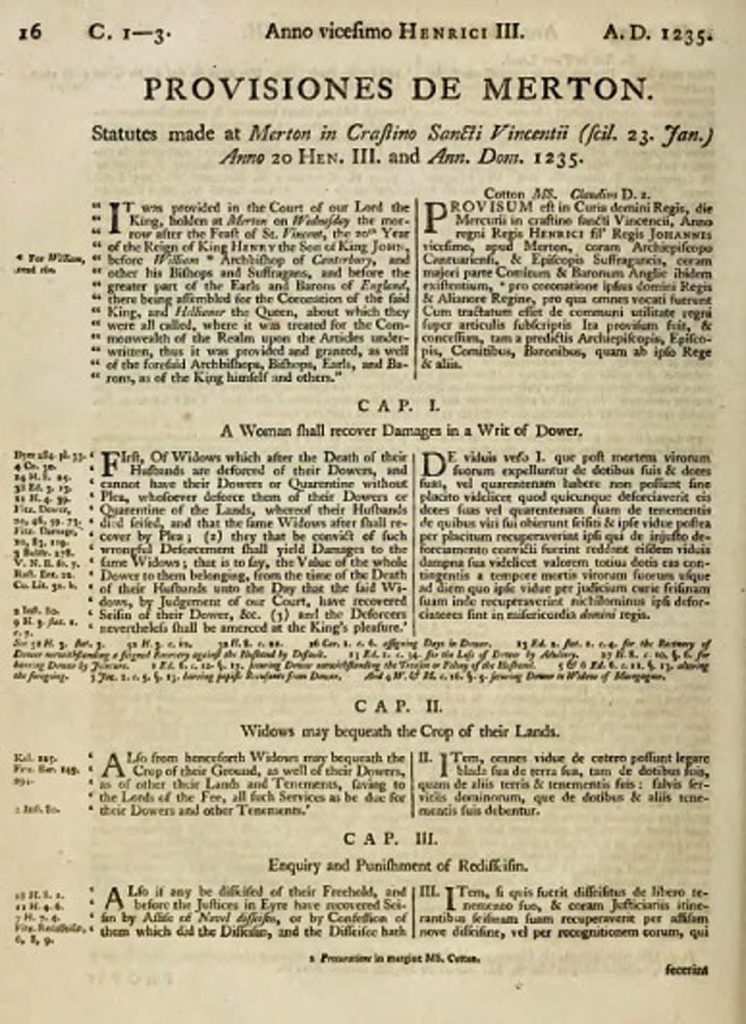

Arguably the first statute to deal with common land in England was the Statute of Merton in 1235. This was passed by Henry III and allowed a lord of the manor to inclose common land (so long as sufficient pasture remained for his tenants), and set out when and how manorial lords could assert rights over waste land, woods, and pastures against their ten-ants.

Background to the Commons Act 1965

During and after the Second World War there was an even greater need for productivity in agriculture. Many commons had been ploughed during the war to provide more growing areas for food. In the early post war years there was a concern that this inclosure and abandonment of common rights was becoming a serious threat to the country’s common land. This coupled with a recognition that green areas played an important role in the health of the nation at a time of increasing urbanisation led to a Royal Commission being established in 1953 to enquire into whether any changes were needed in the law to promote and balance the needs of owners of land, commoners and the enjoyment of the public. It was chaired by Sir William Ivor Jennings. The Royal Commission reported in 1958 and recommended legislation to promote:

- registration of common land and town and village greens,

- public access, and

- improved management.

Key features of the Commons Act 1965

It was not until the introduction of the Common Act 1965 that any of the Royal Commission’s recommendations were enacted. The 1965 Act provided for:

- the registration of common land and greens; and

- a record of commoners’ rights.

The aim was to have definitive registers. Commons registration authorities were set up to create the registers. These authorities were usually county councils and between 1967 and 1970 they accepted applications for registration of land as common land or greens.

If an application was unopposed the land would automatically be registered as common land or as a green. If there were objections, the application would be referred to a Commons Commissioner for determination.

A failure to register land as common land meant that the land was deemed not to be com-mon land after 4 July 1970. The same applied to commoners rights – failure to register them meant they were no longer recognised as enforceable rights.

Problems with the 1965 Act

The 1965 Act was deficient in many ways:

- Land was mistakenly registered as common land

- Common land was missed out or overlooked

- Some grazing rights registered were far in excess of the capacity of the particular common for grazing

- There was limited recourse for correcting mistakes in the register

- It did not implement recommendations on the management of common land

- It failed to introduce public access to common land

Public access on Common Land

Although in 1958 the Royal Commission had recommended a right of public access over common land it was not until the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 that a public right of access on foot over registered common land was granted.

Commons Act 2006

After several more public consultations and government papers the Commons Act 2006 was introduced. The emphasis with this Act was on sustainability. It provided for:

- The establishment of commons councils with powers to regulate grazing and other agricultural activities

- Common registration authorities to bring their registers up to date and to correct mistakes in the registers

- The prohibition of severance of commoners rights – this means that rights of common cannot be sold or leased separately from the land which has the benefit of them. For ex-ample, let’s say that Fred owns a property known as Whiteacre. This property is registered as having rights of common. If Fred sells this property to Molly, Molly will be able to exercise the rights of common. If Fred kept the property, Molly could not buy or rent those rights from Fred.

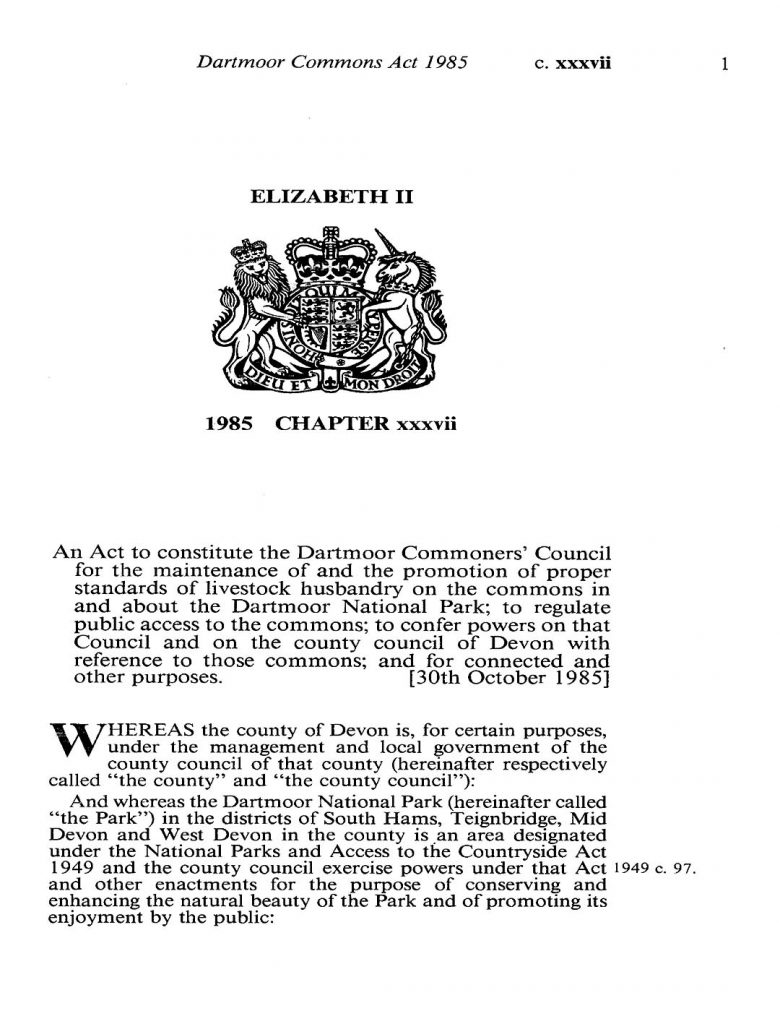

Dartmoor Commons Act 1985

A significant part of Dartmoor National Park is common land: 37% amounting to approximately 35,882 hectares in total. The common land comprises:

- The Forest of Dartmoor;

- Commons of Devon; and

- Some manorial commons.

There are 92 separate common land units with approximately 850 registered commoners. It is estimated that less than a quarter of these commoners are farmers who continue to use the land for grazing. The National Park Authority was instrumental in paving the way for a Dartmoor Commons act. In its first National Park (Management) Plan in 1977 it committed to assisting the commoners to achieve a sound management system and to ensure that this management system had legislative force. It worked closely with Devon County Council and commoners to achieve this but the private members bill failed at its second reading in the House of Commons in 1980. During the debate in the Commons, Anthony Steen (then MP for Liverpool, Wavertree) was a strong objector to many parts of the bill. On the issue of a statutory right of public access he said:

“The Bill seeks to regulate, control and impose so-called order when the moor has flourished for years without such order. Some of my hon. Friends have explained why the public need a statutory right of access, but since Williams the Conqueror people have managed very well without that right. One wonders why the county council suddenly feels that it should be introduced now”

A revised bill was finally passed in 1984. Anthony Steen (now MP for South Hams) was now instrumental in promoting the new bill. He spoke at great length during the Commons debate on 24 June 1984:

“… the background to the Bill. It has been talked about for eight years or more. The problem is the misuse of 100,000 acres of common land by massive overgrazing on the periphery and massive undergrazing in the more inaccessible parts of the moor. The deterioration in shepherding and an increase in the number of animals turned out have caused the problem. … By 1976, the 1,500 commoners were largely agreed that something had to be done, but the first Dartmoor Bill that was brought before the House in 1980 fell, largely because it got the balance wrong between agricultural interests and environmental and conservation interests.

…is legislation needed? All hon. Members must ask themselves that question when a private Bill comes before the House. I have repeatedly asked the commoners the same question. Do they really want more rules and regulations for Dartmoor? Does Dartmoor deserve a Bill? Is there no other way of sorting out their problems? The commoners, who have grazed the moor since the Black Prince restored their pre-Conquest rights in 1336, adamantly answer, “No. Legislation is the only way forward.” That is largely because of the decline in, and the loss of impact of, the old manorial courts to which the commoners used to bring their grievances and which affected all the commons of Dartmoor.”

Creation of a Dartmoor Commoners Council

The Act provided for the creation of a Dartmoor Commoners Council, which would be made up of between 26 and 28 members. The membership is made up as follows:

- each quarter elects five commoners – all must be from different associations and one of the five must be a ‘small grazier’ with a right to graze less than ten livestock units (each unit equals one adult cow or pony or five sheep).

- two members from the National Park Authority

- one representing the Duchy of Cornwall

- one vet

- two landowners of the commons

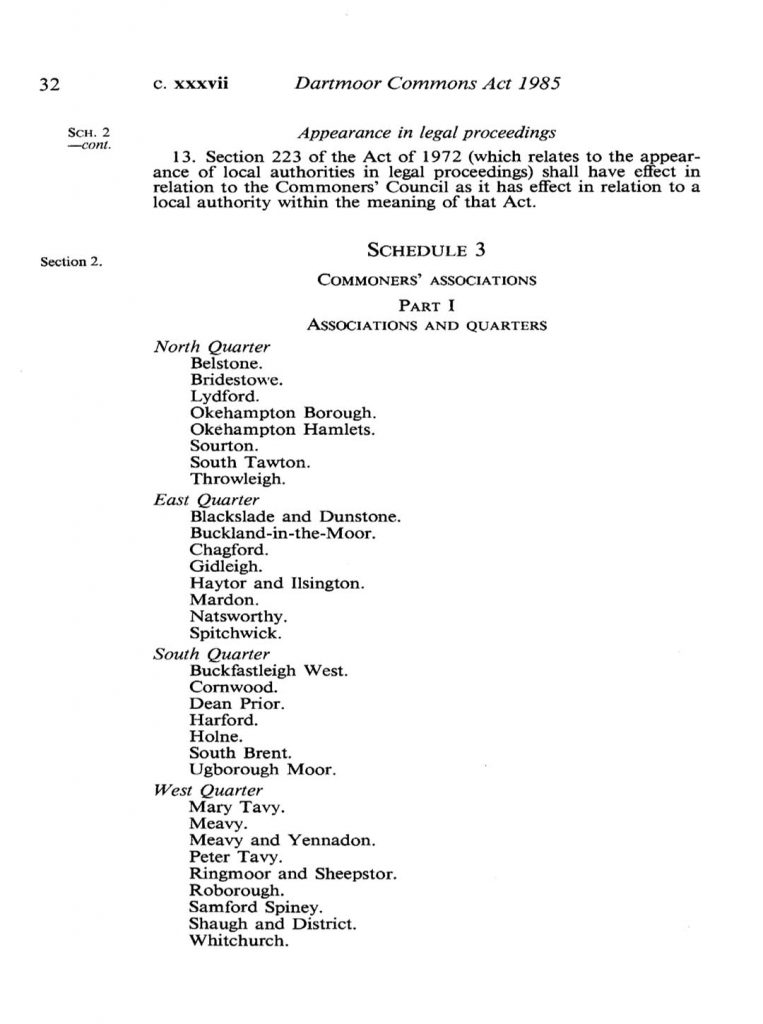

The 1985 Act provided for the Dartmoor Commons to be divided into quarters (north, south, west and east) and for each quarter to have its own smaller commoners associations. As can be seen from Schedule 3 of the Act, the Chagford commons are part of the East Quarter.

The main purpose of the Council is to make regulations to ensure:

- good livestock husbandry

- the maintenance of the health of the animals kept on the commons

- the commons are not overgrazed

It maintains a register of commoners and animals grazing the commons. It also enforces the regulations through appointing officials known as “reeves”.

It is financed by a fee levied on active graziers (72 pence per livestock unit) and non-active right holders (12 pence per livestock unit).

Open access on Dartmoor Commons

The Act secures public access on the Dartmoor commons.

“…the public shall have a right of access to the commons on foot and on horseback for the purpose of open-air recreation”- Clause 10