The origins of common lands and commoners’ rights on Dartmoor are not known, but it is likely that they pre-date the Norman period (i.e. before 1066). Under pressure from increasing population, peasant farmers started to settle on the fringes of what was by then waste land of which there were no clear ownership, but which provided extensive grazing. They would have been followed by estate-owning lords who would have taken up the opportunity to appropriate the common grazing lands closest to them and carving out unenclosed moorland adjacent to their estates. This enabled lords to have control of grazing and to offer grazing rights, introducing charges to others for grazing on “their” land. Also lords could start charging rents from colonists who settled on the common lands. These colonists may have previously been free, but would attach themselves to a lord for protection, thus becoming tenants, which involved a range of mutual obligations. Furthermore lords could then be able to impose more order on a hitherto lawless country.

Venville rights

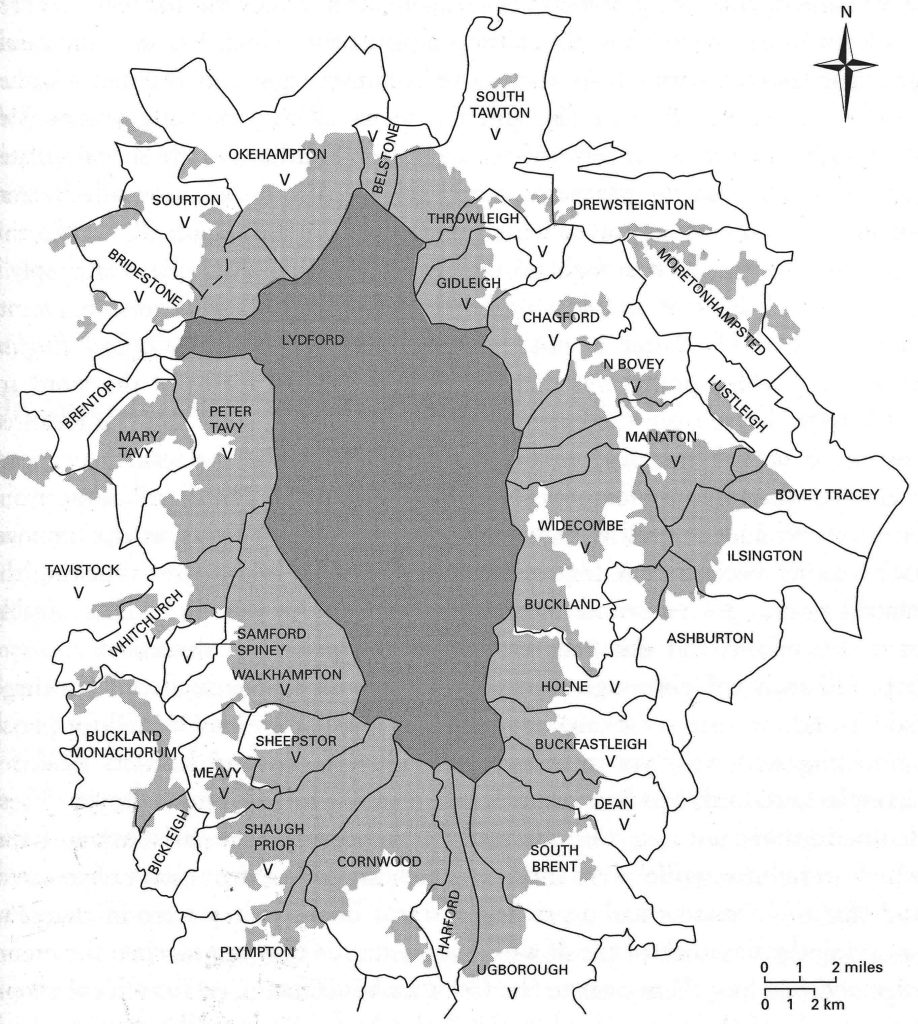

The “venville” parishes are marked with a “V”.

Chagford, along with most the other parishes bordering the central moor were termed “venville” parishes, which meant that most of the property occupiers of those parishes enjoyed certain common rights in the central moor, the former Forest of Dartmoor, owned by the Duchy of Cornwall. These were mostly grazing rights – exercised for a small fee per animal – and allowed day-time grazing for as many animals as could be overwintered on a particular farm. This important restriction prevented overstocking. The venville rights on the Forest would have been in addition to rights enjoyed on the outer moors.

Making agreements on common rights

During the Middle Ages there were seven manors in the parish of Chagford; in some cases the estates extended beyond the parish boundaries. It is likely that they all had pieces of waste or moorland as part of their estates on which tenants and freeholders would have rights. In many cases these rights were enjoyed freely. However, where records do exist on this subject for this period, they usually emphasise mutual obligations. For tenants, such documents were valuable in that they confirmed long-established rights while for the lords these agreements upheld their rights of ownership and proof of their good lordship in granting privileges to their tenants.

Several documents of this nature survive for the manor of “Shapley Hellion”, which is probably the site of Higher and Lower Shapleigh in Chagford (or possibly another, nearby Shapley, but in the parish of North Bovey). Its location on the south-west edge of the parish is right next to Chagford Common. A charter from 1331, signed on 12th June between the lord of the manor, John Proutz, and Richard de la Lane sets out rights for Richard and his obligations in return. We cannot be sure that this is representative, but it could be a typical agreement to confirm commoners’ rights.

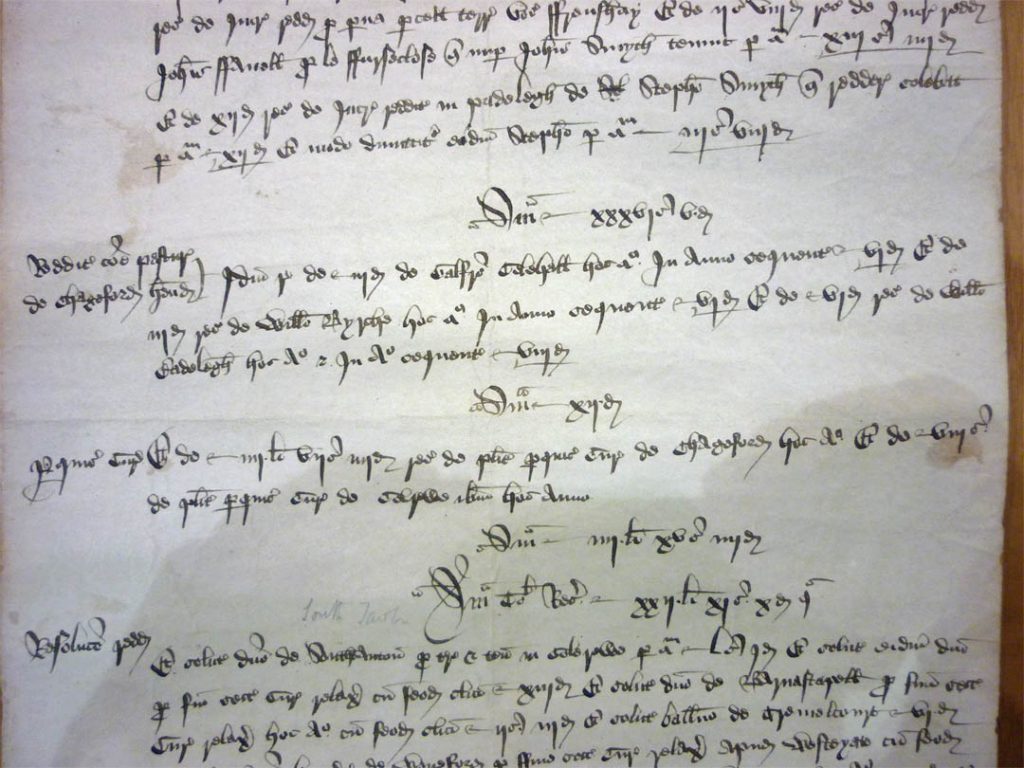

The 1331 charter extract

Also give etc to the same Richard, one day’s work for turves

in my moor of Shapelegh in the place to put and dry them with entrance – exit

to the same

Also common pasture through all of my [Waste?] of Shapelegh but must

meet expenses in grazing them, especially goats and pigs

And sufficient rushes, gorse, bracken turves on the same waste with

free travel to the same waste, to go and return

Witnesses: Walter de Wrey, Hugh de Podenenne, John Parebyn,

Thomas Piers

Given at Shapelegh on Weds next after feast of St Barnabas the Apostle

(i.e. 12 June 1331)

So Richard is here confirmed to have rights of pasture, turbary and estover, as well as the right of access and, it seems, space to stack and dry his turves as well. Note the concern about meeting the expense of grazing goats and pigs, both likely to be more destructive to land than sheep or cattle.

South Teign Manor

South Teign Manor extended over part of Chagford and beyond. A large collection of its mediaeval manorial records still exists. Some of these documents have references to the regulation of common rights. In this example there are references to “pannage” and common grazing for different kinds of stock.

Regulation of common rights on for South Teign Manor, 1343

Likewise the bailiff shall make attachments for grazing and pannage in the lord’s wood from Michaelmas until the Thursday next before the feast of All Saints, excepting attachments for the cows … heifers, foals of the tenants of La Wood and Horslake who can common with the said beasts in the said time and with all kinds of beasts at whatever time of the year.

Manor of Chagford receipts, 1466-7

Among the receipts listed in this record from the manor of Chagford there is notice of a considerable rent increase for the grazing on the lord’s commons in Chagford. This probably implies growth of demand for grazing land, linked to the rise in the population of the town that is known to have occurred at this time.

Rent for the common pasture of Chagford. The same answers for 3d from Geoffrey Colehall this year. In the following year 6d. And 3d received from William Byrche this year. In the following year 6d. And for 6d received from William Cadelegh this year and in the following year 8d.

Transhumance on Dartmoor

The practice of taking cattle and sheep to graze on the open moors has probably been continuous for thousands of years, but we have no record of it until the 13th century when the Duchy of Cornwall started to keep detailed records of sums of money taken from graziers from the Devon lowlands using the moor for their flocks. In May graziers, or their servants, would drive their flocks up to the moors from the lowlands using a network of drove roads, many of which still survive today. This movement of thousands of cattle has been called the “red tide”, referring to the Red Devon cattle which were one of the standard breeds in the past. The flocks would then return to their owners’ lands in August and September. The Duchy employed stewards who would supervise allocations and collection payments, probably subcontracting the work out to local people who lived on the edge of the moor. These farmers would also act as middlemen for the distant graziers. By sending much of their stock to graze on the moor during the summer, farmers could then grow crops and hay in their own fields, essential for subsidence and for feeding the stock at home over the winter. While most of the evidence for transhumance relates to the Duchy-owned central moor, it is probable that the outer moors, owned by manorial lords would have maintained similar income-generating practices.

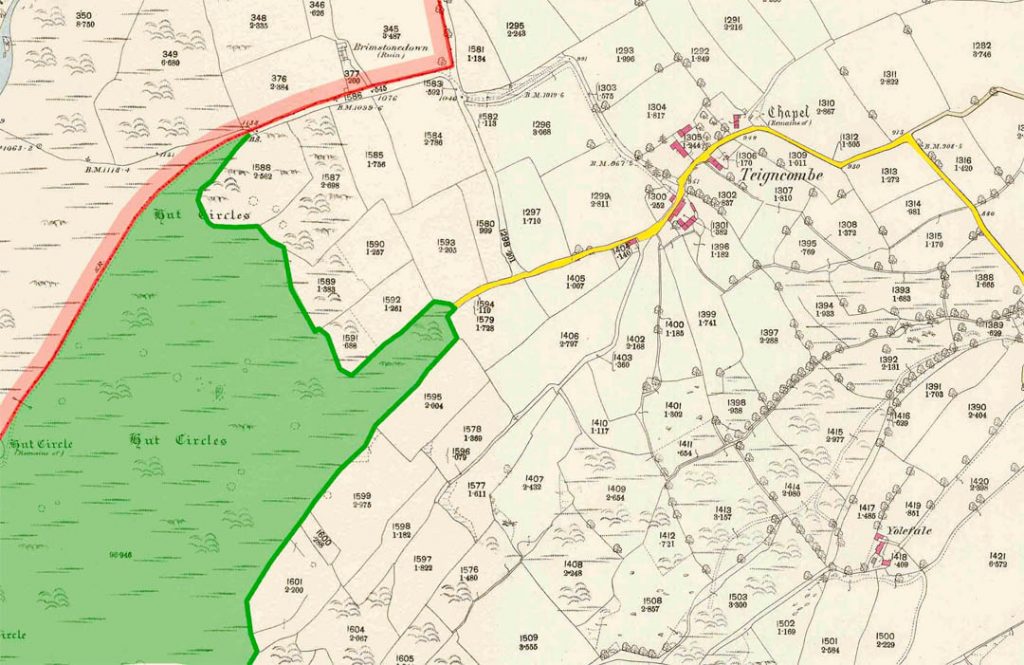

Trackways to the moor

There are number of ancient routes of access to the open moor of Chagford. These would have been used by local farmers and commoners, but also as the routes to moorland grazing for the large herds belonging to lowland graziers, a curse for the “red tide”. One delightful track that still exists as a public right of way is Teigncombe Lane, which turns off the road now leading to Gidleigh Park, gaining height past Teigncombe and then up onto the moor not very far from Kestor. As the map shows, the moorland funnels down into the end of the lane, at the moor gate, thus providing a corralling space for controlling the animals as they first came to the moor or bunching them together before they were driven back down the lanes to the lowlands.